Pragmatics

1. What is Pragmatics?#

Pragmatics is difficult to define in concrete terms. In linguistic research, there are various approaches to how pragmatics can be addressed.

On the one hand, there is the Anglo-American view on pragmatics, where pragmatics is defined as:

Pragmatics is the systematic study of meaning by virtue, or dependent on, the use of language. (Huang 2007, 2013c, 2014:2, 2016)

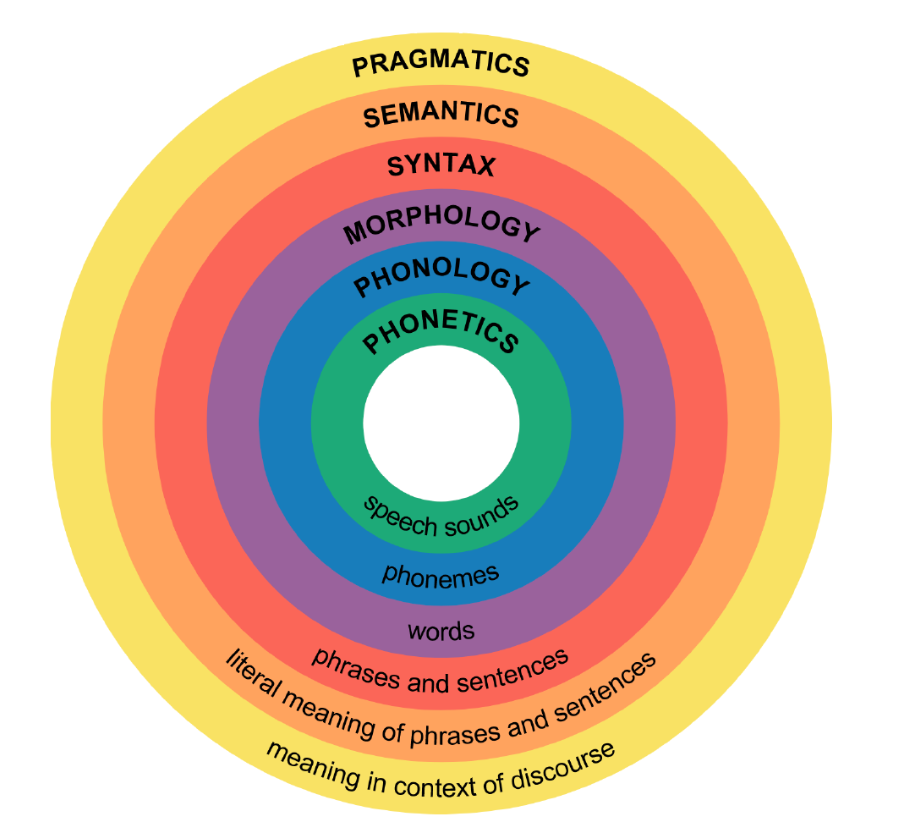

Within this approach, pragmatics exists in a linguistic theory where there are a number of core components such as phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics. Thomas C. Scott-Phillips illustrated this approach in his essay "Pragmatics and the Aims of Language Evolution":

He defines pragmatics as the outermost, and thus the most abstract layer of a language. According to Scott-Phillips, pragmatics carries the meaning of a statement in the context of the conversation. On the other hand, there is the *European Continental* view on pragmatics, where pragmatics is defined as:

He defines pragmatics as the outermost, and thus the most abstract layer of a language. According to Scott-Phillips, pragmatics carries the meaning of a statement in the context of the conversation. On the other hand, there is the *European Continental* view on pragmatics, where pragmatics is defined as:Pragmatic is a general function (i.e. cognitive, social, and cultural) perspective on linguistic phenomena concerning their usage in forms of behavior. (Verschueren 1999:7, 11, 1995:12)

We can benefit from both of these approaches to get an understanding of the concept of pragmatics. As a conclusion, we can combine both into this very simple definition:

Pragmatics is the study of language use in context. (Huang, 2016)

To understand pragmatic contexts, it is not enough to just look at a sentence. It is always necessary to consider the contextual circumstances as well. In this article, we will mostly focus on the Anglo-American structure to explain some of the central concepts of pragmatics, but with the European Continental view in mind.

2. Central Concepts of Pragmatics#

To find a useful way to handle language regarding pragmatics, we have to find rules to divide this major field into smaller concepts. Since language is a flexible system and is constantly changing, those can't be fixed categories. But a rough categorization can help to handle pragmatic problems in NLP in smaller bits.

By using a combination of "The Oxford Handbook of Pragmatics" and Stephen C. Levinson's book "Pragmatics" we tried to segment pragmatics into the following central concepts:

- Conversational Implicature

- Presupposition

- Speech Acts

- Reference and Deixis

- Conversational Structure and Political Communication

In the following, we will briefly explain those concepts using mainly "The Oxford Handbook of Pragmatics" as well as a few other resources. These can be found in the further reading section. To explain how those concepts work and why pragmatic search is still a major problem in Natural Language Processing, we will give you some examples in the following sections.

2.1. Conversational Implicature#

The conversational implicature can be defined as an additional meaning of a statement that is not apparent from the literal meaning but must be inferred from the context.

For example:

A: "I'm out of milk."

B: "There's a supermarket next door."

The answer B gives A doesn't make sense if you're not aware of the fact that you can find milk inside a supermarket. Therefore, it is implicated by B that A has this knowledge and knows what to do with it concerning A's sentence.

This shows that a conversational implicature is a part of what a speaker means, but not part of what the sentence means.

The implicature should not be confused with the term implication. Implication is a term used in semantics to represent connections that can be concluded without any context but from having some basic knowledge.

For example:

"The cat lies on the carpet."

This implies that the carpet lies under the cat. The only knowledge we need to comprehend this implication is how to revert this sentence semantically.

Paul Grice defined implicature as a cooperative principle:

The cooperative principle implies that when we communicate, we are effective and cooperative. We also assume the same from our conversational partner.

Through Grice's pragmatic theory, he also introduced the attendant maxims of conversation based on the cooperative principle. You can find more about that in his book "Studies in the Way of Words".

The four maxims he defines are rules which can predict how to stay true to the cooperative principle:

- The Maxim of Quantity is about being informative.

One should make their utterance as informative as the current conversation purpose requires, but not more than that. - The Maxim of Quality is about being truthful.

This means one shouldn't say anything they think is false, but also shouldn't say anything they can't give adequate reasons for its truth. - The Maxim of Relation is about being relevant.

One shouldn't say anything that isn't relevant to the conversation. - The Maxim of Manner is about being clear.

This means obscure language, ambiguity, and prolixity should be avoided in favor of proper language.

By following the cooperative principle we can make conclusions and thus implicature. Often those maxims are broken on purpose, to get a specific effect.

- Violation of the quantity maxim

- Tautologies: "It is what it is", "voll und ganz"

- Violation of the quality maxim

- Irony/sarcasm: "Oh great..."

- Understatement/overstatement: "I was barely drunk after all.", "This will take ages."

- Lying

- Violation of the relation maxim

- Sudden change of subject

- Evasion: "What is the capital of Germany?" - "It is not Paris."

- Violation of the manner maxim

- Euphemism: "I'm not mad. I'm just ... well, differently moraled, that's all."

- Obscure language: "Where were you? Did you get milk?" - "Maybe I did, maybe I didn't."

These maxims are not an ideal categorization but they can help to understand implicature and to determine the problems with it in NLP.

2.2. Presupposition#

Presupposition can be defined as the implicit assumption that the counterpart has certain knowledge about a given statement.

Examples:

- Lisa stopped going to the gym.

Presupposition: Lisa was going to the gym. - Are you vegan now?

Presupposition: You didn't eat vegan before. - Did you meet up with Louisa?

Presupposition: Louisa exists.

Linguistic research tries to distinguish between semantic and pragmatic presupposition. While the semantic presupposition focuses on the truth of a statement, the pragmatic presupposition is concerned with whether a statement is adapted to the world knowledge of the counterpart.

Thus, in the case of "Joe Biden won the US election" the semantic presupposition would be that there is a person named "Joe Biden" and that there is an election in the US. The pragmatic presupposition, on the other hand, would be that the writer of the sentence assumes that the receiver knows who Joe Biden is.

It is often difficult to separate the semantic and pragmatic presuppositions because they often go together. Therefore, it is useful to consider both equally.

To detect a presupposition in written text, one can look for certain lexical items or linguistic constructors that trigger a presupposition. The following were defined by Stephen C. Levinson in his book "Pragmatics":

| Presupposition trigger | Description | Example | Presupposition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definite descriptions | A noun-phrase or a singular common noun with a proper description. | "The king of France is old." | There is exactly one person who is the king of France. |

| Factive verbs | Verbs that assume that their object, mostly subclauses, are a fact. (e.g. be aware of, regret that, realize that, be sorry that, be glad that, etc.) | "Julia realized that she was in debt." | Julia is in fact in debt. |

| Implicative verbs | Verbs that imply an underlying attempt. (e.g. happened that, managed to, forgot to, avoided to, etc.) | "The politician did not win the election." | The politician ran for office. |

| Change of state | Verbs that imply a change of a previous situation. (e.g. start, finish, etc.) | "He stopped smoking." | He did smoke before. |

| Iteratives | These imply a previous existence of a situation. (e.g. again, another time, return, repeat, etc.) | "They met again." | They met once before. |

| Temporal clauses | Clauses that explain the background situation in the following sentence. (e.g. after, during, while, since, before, etc.) | "While she was working, he was sick at home." | She is working. |

| Cleft sentences | Sentences that highlight certain information and declare it as background informative. | "It was not Andrea, who murdered Harold." | Harold has been murdered. |

| Comparisons and contrasts | Comparative constructions can imply background information about the compared object. | "He is an even better golf player than Tiger Woods." | Tiger Woods is a golf player. |

| Counterfactual conditionals | Implying that something happened by negating it. | "If she hadn't missed the stop sign, she'd still be here." | She did miss the stop sign. |

| Questions | Specific questions that are phrased to get a concrete answer. | "Who is the Queen of England?" | There is someone who is Queen of England. |

| Possessive case | Relations can imply the background information about possession. | "Rosie's dog is very cute." | Rosie has a dog. |

These triggers can be a helpful clue while processing texts that include presuppositions. The transitions between pragmatic concepts can be fluid, as already mentioned in the previous section.

2.3. Speech Acts#

Speech acts are one of the most important fields in pragmatics and, for a long time, were not taken into account as much as other fields. This field analyzes which actions a speaker intends based on what they say.

"The Oxford Handbook of Pragmatics" defines “speech acts” as follows:

(...) speech acts are more like moves in chess, whose meanings are circumscribed by rules and expectations. Trying to understand how utterances can have these abstract action-like properties, how they are coded linguistically, and how we recognize them are some of the core issues in this domain.

Since many users make their queries intuitively by using speech acts, and phrase their queries similar to their speech habit, this area can be particularly important for Information Retrieval. Especially concerning the everyday use of search engines.

In his book about pragmatics Searle, following Austin(1962), differentiates four acts associated with speech as communication:

- Utterance Act: The act of producing an utterance by means of phonological and grammatical rules of a language.

For example: "Peter does smoke." as a spoken sentence - Propositional Act: The act of referring to things (reference) and ascribing properties to them (predication).

For example: "Peter smokes." Reference to Peter and attribution of the property of smoking. - Illocutionary Act: The function that a predication act takes in communication.

For example: Assertion that Peter smokes. (other examples would be inquiring, commanding, promising, etc.) - Perlocutionary Act: The consequences and effects of illocutionary acts.

For example: Addressee believes that Peter smokes.

He further classifies the illocutionary acts into 5 categories:

| Category | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Representatives | Committed to the truth of the proposition expressed | "It's snowing right now." |

| Directives | Attempt to cause an action | "Pick that up, please!" |

| Commissives | Committing to a future action | "Promise me you won't do that again." |

| Expressives | Expressing a mental state | "Thank you for your help." |

| Declaratives | Lead to a change of state of an entity in the structure of social institutions | "I quit!" |

It very much depends on the domain to what extent speech acts can play an important role in Information Retrieval. Since this is a rather complex field, it is always helpful to weigh how much benefit you can get from taking it into account.

2.4. Reference and Deixis#

Since reference and deixis are very closely related topics, we decided to summarize them in one section. A reference is always dependent on the sentence in which it appears and cannot be understood without context.

For example:

"Are you there yet?" - "No, I'm still at the cafe."

Without any more information, it is impossible to know exactly where "there" is.

We can divide the pragmatic reference into two categories:

- Deictic reference

- Anaphoric reference

Deictic Reference

The word deixis is derived from ancient Greek and means "to show" (Indexicality is also often used instead of deixis). Deictic reference is always found outside of a text. Thus, one can say that without an apparent textual context, a reference is most likely deictic.

A rough distinction is made between the 5 categories of deixis:

- Personal Deixis concerns the identity of the conversation partners (pronominal system)

For example: "I, you, he, she, ..." - Social Deixis forms of address

For example: "you", "ladies and gentlemen" - Temporal Deixis concerns temporal orientation

For example: "today, yesterday, tomorrow, ..." - Local Deixis concerns spatial orientation

Can be distinct between positional ("here, there, ...") and dimensional reference system ("in front of, behind of, left, right, above, below, ....") - Text & Discourse Deixis refers to parts of the preceding or following text

For example: "What I'm trying to say is that..."

Specifically, local and tense deixis can vary greatly depending on the language. For example, in Japanese, there are references to objects that vary according to speaker position: koko, soko, asoko.

Anaphoric Reference

The word anaphoric is also derived from Greek and means "to carry up" or "to refer to something.". An anaphoric reference refers to a preceding part of a sentence. This inner textual reference can be inferred from the text without any special prior knowledge.

For example:

A: "I met Lisa earlier. She looked really relaxed." B: "That's what I thought, too. I think she just came back from her vacation."

So from "Lisa" to "she" is anaphoric, because we can get the reference from the text. The same goes for "That's (what I thought, too)" and "(I think she) just came back from vacation", which both refer to "She looked really relaxed". These are anaphoric references.

Less common is the case of pre-reference, the so-called cataphoric reference or cataphor.

For example: "I should have known; the task is just too hard."

Other references that are difficult to fit into these two categories would be:

- proper nouns ("Montblanc", "France").

- definite identifiers ("the highest mountain in Europe", "Tintin's dog")

- generic names ("cat") or substance names ("milk"), which only become referential in connection with other referential expressions ("our cat", "the milk over there")

While some of these references can be solved by looking at more of the surrounding text, there are some - for example those which refer to objects or persons outside of the text - that are nearly unsolvable without the right context.

2.5. Conversational Structure and Political Communication#

Although these two topics are often handled separately in the literature, we have decided to combine conversation structure and political linguistics under one heading, since they do play a minor role in our experiments.

Conversation Structure (also Conversation Analysis)

In conversation structure, we study and analyze how people carry on conversations with each other.

Characteristics such as constitutivity, processuality, interactivity, methodicity, and pragmaticity are examined in more detail.

This analysis takes place on different levels; the factual level, action level, social level, appeal level, the modality of the conversation, and the establishment of reciprocity.

Political Communication

Political communication studies how language and politics function in various contexts. For example, it examines the relationship between language and the political system, language and the political process, and language and individual political fields.

Both areas are mainly concerned with spoken language, which is why they are of little importance for extracting information from documents. We could consider them when searching typed conversations, but since we haven't experimented on that yet, it's not as relevant as the other concepts.

3. Problems with Pragmatics in NLP#

When dealing with pragmatics in Information Retrieval, the most central subject is context. This can be viewed from two sides, the side of the participants (e.g., conversationalists, listeners, etc.) and the side of the analysts (e.g., linguists, sociologists, philosophers, etc.). The analytical side is more interesting to us in the context of the search. When approaching context, we can try to divide three levels regarding Information Retrieval:

- Linguistic Context:

This can also be understood as corpus information (what information can be extracted from the corpus). This includes all contexts that can be extracted using the linguistic rules of a language.

For example: If there is only information about the zodiac signCancerin the corpus, it won't find anything about the deadly illness. - Cognitive Context:

This is often also interpreted as world knowledge (or also basic knowledge; common knowledge about general topics). This includes numerous, still largely unexplored, processes that take place in the minds of participants during a conversation. Unspoken things that are assumed as knowledge.

For example: If someone searches for "cancer month", the basic knowledge should lead to the zodiac sign and not the illness, because it is likely a search request for the zodiac sign. - Social & Sociocultural Context:

This could also be referred to as user information. This includes, for example, how old a user is, where the person is, what he or she mostly searches for, and which topics are relevant for the person.

For example: If someone tends to search for their horoscope every day, it is far more likely they want an article about the zodiac signCancerthan the deadly illness.

When we fail to consider the importance of context from the pragmatics, it can easily happen that relevant information is not found. But since pragmatics is such a large field, and so many variables must be taken into account, it is very difficult to implement all of these into a search engine. There are different approaches to handle pragmatic problems, for example, creating an ontology - like a knowledge map - around different domains and teaching the search engine to cross-check with these while searching. But since there is, as yet, no way of making those fully automatic, (although there are some approaches in the making) it is always burdened by high costs in both time and money.

4. Further Reading#

If you're interested in more detail about pragmatics in general, you can look into our main sources below. Please be aware that most of them are not free to access, but some of them are available through student accounts.

- Grice, P. (1989). Studies in the Way of Words. Harvard University Press.

- Huang, Yan (2007). Pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Huang, Y. (Ed.). (2017). The Oxford handbook of pragmatics. Oxford University Press.

- Langshaw, A. J. (1962). How to do things with words. Cambridge (Mass.), 2005-168.

- Levinson, S. C. (1983). Pragmatics Cambridge University Press. Cambridge UK.

- Meibauer, J., Demske, U., Geilfuß-Wolfgang, J., Pafel, J., Ramers, K. H., Rothweiler, M., & Steinbach, M. (2002). Pragmatik. In Einführung in die germanistische Linguistik (pp. 208-250). JB Metzler, Stuttgart.

- Schütze H. & Zangenfeind R. (2020). Einführung in die Computerlinguistik - Pragmatik (Lecture Slides). Center for Information and Language Processing, LMU, München.

- Scott-Phillips, T. C. (2017). Pragmatics and the aims of language evolution. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 24(1), 186-189.

- Searle, J. R., Searle, P. G., Willis, S., & Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language (Vol. 626). Cambridge university press.

- Verschueren, Jef (1999). Understanding Pragmatics. London: Edward Arnold.

Acknowledgements:

Thanks to Kenny Hall for proofreading this article.